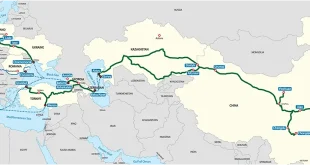

Given Europe’s need for Russian natural gas and the lack of easily available alternatives for Russia’s energy resources in the European market in the short term, solutions to political disagreements between Europe and the Middle East are more vital now than ever.

Energy flows—imports and exports—constitute a major element of foreign policy for some nations, as well as a key method for attracting foreign investment. Energy flows are of such importance in the modern world that many states have incorporated them into their broader diplomatic goals. The centrality of energy resources to economic life strengthens the hand of energy-exporting nations and makes their actions relevant to other areas of foreign policy. It should be noted that a country’s energy diplomacy depends to a high degree on what it seeks to achieve from its foreign policy. For energy diplomacy to have an impact on the foreign policy environment, countries must focus on soft power, the participation of and interaction between major players, any mutual interests, and the fundamental concern—maintaining one’s position, control, and influence in the international system.

Energy Superpower

In the twenty-first century, the world has retained its insatiable demand for energy, whether it be “fossil fuels” such as coal and oil, or emerging “greener” forms such as wind and solar. Countries referred to as “energy superpowers” play key roles in the global energy market. The term “energy superpower” describes a state that possesses and has the capacity to export significant amounts of oil, natural gas, coal, and uranium—and, in some cases, renewable energy facilities as well. Energy superpowers maintain high export volumes and have a major impact on trade and the determination of prices. Russia is perhaps the quintessential energy superpower, as one of the largest oil and natural gas producers in the world. Russia achieved its status as an energy superpower between the years 2006 and 2009 after substantial modernization and foreign investment in its oil and gas reserves. As the current crisis in Ukraine shows, Russia has tailored its energy diplomacy to achieve its foreign policy goals. It has placed restrictions on oil exports to countries that it perceives as “unfriendly” to its interests, thereby pressuring these states to restrain their criticisms of Moscow. The Russian example also offers a cautionary tale for energy superpowers. In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, European states have sought to reduce their dependence on Russian energy sources, diminishing the Kremlin’s ability to influence the West in the future.

Indeed, Europe’s attempts to divest from Russian energy led energy expert Daniel Yergin to observe in the Economist that Russia appears to be losing its power in the field of energy. After describing the myriad benefits that energy resources have brought to Putin, Yergin remarks that Russia’s three-decade period of fossil fuel-driven economic growth appears to have ended with its invasion of Ukraine.

In his article, Yergin also refers to the extensive investments by Russian companies in the Russian energy industry over the last 30 years, in addition to investments by Western energy companies in Russia’s energy infrastructure. Russia’s exposure to and dependence on Western investment significantly weakened Russia’s economy when Western countries imposed sanctions. Almost all major Western energy companies pulled out of Russia in the opening days of the conflict, putting Russian oil and natural gas production levels at risk as Russian energy companies struggled to extract their natural resources as efficiently. Moreover, sanctions cripple Russian access to financial resources and advanced technology from the West.

As the world’s second-largest producer of liquefied natural gas, or LNG, Qatar could play an important role in maintaining Europe’s energy security in light of its new relationship with Russia. The linchpin of this strategy, if it is adopted, will be Germany—the largest importer of Russian natural gas. On the eve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, German regulators were on the cusp of approving the controversial Nord Stream 2 pipeline. That pipeline would have brought natural gas directly from Russia to Germany, bypassing Ukraine and other Eastern European countries. The Germans had no choice but to shut down certification and halt the opening of the pipeline after the invasion. However, Germany’s demand for gas has not decreased, and its reliance on Russian imports will continue to be a weak spot in the European Union’s Russia policy. Changing that dynamic requires addressing that dependence by finding other export sources like Qatar.

Last week, discussions between Doha and Berlin resulted in an understanding that Qatar would increase its shipments of LNG to Germany to address the problem. “[The] EU may need Russian gas again this year, but we will not in the future,” a German official said, committing the country to cutting off its supply chain dependency on the Kremlin. Altogether, Germany imported about 142 billion cubic meters of gas in 2021, around 40 percent of which was Russian sourced. Although Qatar’s LNG imports will not be a perfect solution to Europe’s energy problems, as much of its existing production is tied up in long-term contracts with nations in the Far East and it lacks the capacity to increase production enough to meet European demand. Nonetheless, Qatari investment in new LNG export capacity holds the potential to supply more to the EU in the mid-term.

Iran Unlikely to Supply Europe

Iran cannot realistically become a significant natural gas exporter to Europe soon. Domestic energy consumption in Iran reached record highs last January. Iranian power plants, major industries, and the domestic and commercial sectors consumed 788.9 million cubic meters that month. Although the winter season has ended in Iran, meaning that gas consumption should be lower, the production and consumption of natural gas for Iran’s domestic needs precludes any hopes of filling European orders, even if sanctions against Tehran are lifted.

Additionally, for Iran to become an LNG supplier to the European Union, it will require considerable foreign investment and technological development, as Western sanctions have prevented the modernization of its gas extraction technology over the past decade. In essence, to increase production and export, foreign investors with new technologies are essential. To receive those, the Iranian nuclear negotiations in Vienna must first conclude successfully and sanctions lifted.

To compensate for its domestic natural gas needs, Iran has already reduced the amount of gas exported to Iraq and Turkey in recent months, creating many problems for its neighbors. In sum, it is conceivable that Iran might become a natural gas supplier to Europe in the mid- to long-term. However, Tehran must first address other points of contention, such as its ballistic missile program and its support for regional militias, if it is to secure the lifting of other sanctions. Otherwise, Tehran’s lack of access to modern technology and foreign financial resources—problems made worse by its blacklisting by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) —means that it is not a viable option to replace Russian natural gas at present.

Abu Dhabi and Riyadh Maintain their Leverage Over the Oil Market

In searching abroad for alternative energy supplies for Europe, the two most obvious choices are perhaps the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, two of the largest oil producers in the world. The UAE and Saudi Arabia can stabilize the oil market by increasing production capacity; the two powers could even replace part of Russia’s oil in the European market by increasing production, a simple step for Abu Dhabi and Riyadh due to their low production costs. However, even as oil prices have fluctuated wildly upward, Saudi and Emirati leaders Mohammed bin Salman al-Saud (MBS) and Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan (MBZ) have publicly committed to retaining OPEC+’s previous oil targets, a policy that critics claim is far from sufficient to stabilize oil demand.

More concerning still, in mid-March, reports began to circulate that the two leaders had refused to speak with President Joe Biden over the phone to discuss growing energy prices. If true, these rumors indicate a major snub to the American leader. Saudi and Emirati diplomats have struck a slightly more conciliatory tone in public; UAE ambassador to the United States Yousef al-Otaiba said in a statement that Abu Dhabi favored higher oil production and would raise the issue with OPEC+. Moreover, seeking to dispel the rumor of the phone call, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki announced that Biden had had no plans to speak with MBS. However, the UAE and Saudi Arabia’s visible reluctance to follow the U.S. line and increase oil production has led them, by and large, to refuse to support the Western position on Ukraine. This applies especially to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which are each concerned about the security of their nations in the aftermath of the U.S. departure from the Gulf. In doing so, both Abu Dhabi and Riyadh have put their relationship with the United States to the test.

Exports of liquefied natural gas from the United States to Europe have risen sharply as a direct result of the crisis in Ukraine. The importance of the European energy market to the United States is very clear. Washington appears prepared to take the European energy market away from Russia wholesale, although its ability to do this in practice is uncertain.

Meanwhile, increasingly sophisticated attacks by Yemen’s Houthi rebels on Saudi (and, to a lesser extent, Emirati) energy infrastructure, most recently on March 26, and Iranian support for the Houthis have raised the issue of infrastructure security in the Gulf. Arab countries in the region have great potential to stabilize the energy market—a fact that the United States and other Western countries should observe and work towards achieving. By the same token, the West has expressed a lack of interest in GCC states’ national interests and security concerns—particularly surrounding the new nuclear agreement with Iran. Some GCC members have objected to reinstating the JCPOA on the basis that it offers sanctions relief without addressing Iranian support for militias such as Hezbollah and Houthis’ Ansar Allah. This disinterest could face the GCC closer to Russia and China.

If Europe is serious about energy diversification away from Russia, it can find reliable suppliers among Arab countries, but it must take Arab concerns seriously. Given Europe’s need for Russian natural gas and the lack of easily available alternatives for Russia’s energy resources in the European market in the short term, solutions to political disagreements between Europe and the Middle East are more vital now than ever.

Within Russia, Putin, who has always paid special attention to the role of energy in Russia‘s foreign policy, should henceforth look for other factors that may grant Russia leverage when conducting foreign policy. Major energy-consuming countries have invested heavily in the infrastructure needed to import energy. The process of sending energy resources from one nation to another is complicated and requires both huge energy reserves and inputs of advanced technology. It is unclear whether Russia will be able to obtain the latter if it maintains its current course in Ukraine. If Russia’s obstinacy over Ukraine persists, the global energy market may say goodbye to Moscow as an energy superpower. www.gulfif.org