Washington has deliberately increased its own LNG exports to Europe, and U.S. diplomats are trying to persuade Qatar to assist in meeting part of Europe’s natural gas needs, supporting the EU’s energy security as a traditional U.S. ally.

The ongoing tensions in Europe between Russia and Ukraine have contributed to an ongoing energy crisis in Western Europe. The countries of the European Union, which depend overwhelmingly on cheap natural gas imports from Russia, have increasingly grappled with the possibility that Moscow might shut off those imports to influence European policymaking in the east – making the flow of energy a national security concern for the EU states. It is difficult to contest the notion that Russia uses its natural gas exports to Europe to achieve political and economic goals, and if the recent tensions between Russia and Ukraine end in war, Russia could threaten to cut off gas supplies to Europe or reduce its gas exports as a way to discourage a European intervention.

Out of Gas

By importing more natural gas and liquefied natural gas (LNG) from other countries, investing more in renewable energy, and accelerating the transition to clean energy Europe can do much to reduce the impact of a possible energy crisis. However, given the current level of production of natural gas, creating overnight a reliable alternative source of Russian natural gas for Europe’s energy needs does not seem feasible. European countries have been facing an energy crisis since the middle of last year, when many restrictions stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic ended and economic activity resumed, which led to greater demand for energy.

Some members of the European Parliament have accused Russia, which supplies about 40 percent of Europe’s gas imports, of using its gas exports as a weapon in crises. Some officials in Europe believe that Russia has reduced the flow of gas through other pipelines to incentivize German legislators to speed up the regulatory approval of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which will transport Russian gas to Germany via the Baltic Sea. Russia has denied these allegations, claiming that the launch of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline would reduce prices by increasing gas exports to Europe and removing existing inefficiencies – such as piping the gas through intermediary countries, each of which presently receives a cut. Russia has repeatedly stated that it has fulfilled all its obligations under existing agreements.

Whatever the truth of Moscow’s statements, the United States has attempted to increase its market share in Europe as well. According to Oil Price, the volume of natural gas imported from the U.S. to the European Union so far this month has been five times higher than imports through Russian pipelines. This is the first time in history that U.S. energy exports to Europe have surpassed those of Russia. Last month, at least 30 liquefied natural gas tankers sailed from the United States to Europe. The European market is a lucrative new opportunity for American exporters, as the energy crisis has pushed European gas prices well above the Asian gas price index. Russia’s low supply and cold weather in Europe have been the two main drivers of rising gas prices in Europe in recent weeks, as Russian gas transfers through Poland and Ukraine have been lower than usual.

Qatar Steps In

In accordance with a seven-and-a-half-year gas contract signed between Germany and Qatar in 2016, Qatar’s QatarGas energy giant exports 4 million tons of gas to customers in Europe. Under the 2016 agreement, Qatar will supply up to 1.8 million tons of LNG annually to the main European energy trading center in Essen, Germany.

Other European Union member countries, which import LNG mostly from Qatar, imported approximately 17.5 billion cubic meters of LNG from countries in the Middle East in 2020, which is about 8 billion cubic meters less than it was in the previous year prior to the start of the pandemic. On the other hand, Russia nearly doubled its LNG supply from 7.8 in 2019 to 14.1 billion cubic meters in 2020.

In 2018, Qatar’s role in Europe’s energy security increased. Seeking a way to reduce the power of the Kremlin’s energy weapon in Europe, Washington has pushed Qatar, the world’s largest exporter of LNG, to increase its exports to the continent. By January 2019, Deputy U.S. Energy Secretary Dan Brouillette told Reuters that the United States was in talks with Doha over European LNG supplies and wanted Germany and other European countries to import gas from the United States and Qatar instead of Russia. He said he had spoken about the issue with Qatari Minister of Energy and Qatar Petroleum CEO Saad al-Kaabi. Qatar announced in September 2018 that it would invest 10 billion euros ($11.6 billion) to strengthen its relations with Germany over the next five years, possibly including the construction of an LNG terminal.

In 2018, during a visit for the Qatari Emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani to Germany, Doha announced interest to work with Germany on the construction of a gas terminal. Meanwhile, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel was keen to co-finance with private sector the construction of LNG terminal and stressed that investing in Europe’s energy sector offered promising opportunities for the development of trade relations with Qatar. Merkel indicated that Germany was already connected to LNG terminals in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Poland, adding that the government was looking to expand its LNG network.

Third-Party Imports

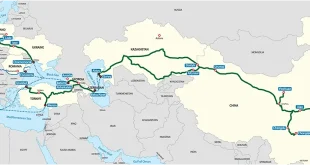

The European Commission has also pursued energy ties with Azerbaijan, another significant exporter of natural gas, to boost supplies to the bloc, EU Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson said on January 22, 2022, after an informal meeting of its Energy Council. On Friday, January 28, Azerbaijani Ambassador to the UK, Elin Suleymanov, announced Azerbaijan’s readiness to increase natural gas production and exports to Europe if needed. According to Elin Suleymanov, Baku can also channel gas from Turkmenistan from fields at the Caspian Sea.

On Wednesday, the International Energy Agency (IEA) attributed Europe’s gas shortage largely to Russia. Fatih Birol, the IEA’s Executive Director, indicated that Gzprom had reduced exports to Europe in the fourth quarter of 2021 when the price of gas was high. To make up for the Russian shortfall, Norway, Algeria and Azerbaijan were pumping higher volumes of gas. The price of crude oil has increased across the world at the end of 2021, contributing to a greater European vulnerability to pressures imposed on both businesses and consumers, and to a record level of inflation in the eurozone. Despite the relatively mild weather and the flow of gas from the U.S., the prices of wholesale gas in the northwestern region of Europe are roughly three times higher than they were in January 2021. According to analysts, a resurgence of cold temperatures and low levels of gas storage may lead to further spikes in prices.

The United States is making a multi-pronged effort to head off the challenge of Europe’s dependency on Russian gas. Washington has deliberately increased its own LNG exports to Europe, and U.S. diplomats are trying to persuade Qatar to assist in meeting part of Europe’s natural gas needs, supporting the EU’s energy security as a traditional U.S. ally. At the same time, Washington has urged Europe to block the start of Russian gas exports through the Nord Stream 2 project, fearing that Putin wants to deliberately increase Europe’s dependence on Russian energy resources through this project.

However, even if Qatar responds positively to Biden’s request, its small uncommitted LNG export capacity and small share of the European energy basket, will not significantly reduce Russia’s share of the European energy market in the short term. Before imports from Qatari can substantially replace Russian ones, Europe needs to substantially increase investments in its energy infrastructure and LNG storage facilities. Moreover, to incentivize Qatar to supply Europe with gas, the EU should consider offering Doha higher prices, or maybe match it with the price offered to the U.S. gas supplies. Finally, these efforts may all come to nothing: given Moscow’s policy of active energy diplomacy in the EU, Putin will not easily accept a decline of Russia’s share of the European energy market, and will likely pursue policies of his own to fight back.

www.gulfif.org