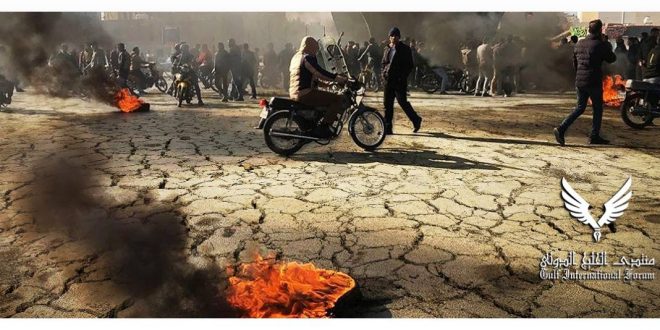

Iran has always struggled with droughts in the past, but the current water shortages have led to major economic hardship – and even waves of protest, testing the government’s ability to provide basic services and maintain order.

Water scarcity is a growing problem across the Middle East. It has grown in importance for a variety of reasons, ranging from climate change to poor governance. This problem has affected more and more people on all continents of the world, but it is particularly harsh today in Iran, one of the hottest and driest regions in the world. Iran has always struggled with droughts in the past, but the current water shortages have led to major economic hardship – and even waves of protest, testing the government’s ability to provide basic services and maintain order. From power outages in June to water supply problems in a number of Iran’s provinces, especially southwestern Khuzestan, the reduction of water resources as a serious concern has touched all aspects of Iranian political, economic, and social life.

The two paths usually followed by Iran to overcome periodic water shortages have been desalination and transfer of water from the Persian Gulf to the central provinces that have suffered the most from recurring droughts. Heavy industry and a large proportion of the agricultural sector in Iran have access to the freshwater of the Persian Gulf, and utilization of freshwater facilitates the protection of valuable groundwater resources. Moreover, this water can be stored and utilized by local rural communities, helping to prevent Iranians in the countryside from moving to the cities in droves. Unfortunately, the water issue in Iran has deep political implications at all levels of society, as it has caused direct conflicts between local areas and the central authorities.

Current Protests in Isfahan

Isfahan, one of the largest cities in Iran, is also one of its key industrial hubs. The city boasts more than 9,000 industrial units and the country’s largest factories, according to the latest statistics of the Statistical Centre of Iran. According to the Isfahan Province Industrial Towns Company, more than 430 towns, industrial areas or workshop units are in the Isfahan province, most of which are in or near the Zayandehrud catchment area. While Isfahan industries, especially steel industries, have frequently spoke about reducing their water consumption, environmental experts contend that the Esfahan Steel Company and Mobarakeh Steel Company, two highly water-intensive industries in water-scarce areas, have no environmental or landscaping justification. The construction of the two factories happened without the necessary attention on their water consumption and environmental impact.

Mahmoud Hosseini, the governor of Isfahan from 2002 to 2006, told the Hamshahri newspaper that “68% of the country’s steel […] is produced in Isfahan,” noting the extreme pollution and environmental destruction that those industries created. In recent years, the steel industry and the refinery have expanded, requiring higher water consumption. Referring to the production of 17 million tons of steel and associated by-products by the Mobarakeh Steel Company in Isfahan last year, Ali Salajegheh, the Vice President and head of the Iranian Department of the Environment, said: “This amount of steel needs about 170 to 200 million cubic meters of water .” The water industry in Isfahan is not limited to steel, but also includes petrochemical development, pottery and brick factories, cement, ceramics, and so on. The construction of this volume of industrial factories and the cultivation of products such as rice show that Iran has not paid any attention to the climate, resources, and water reserves of this province in any meaningful sense, and as a result, Iran is now facing a crisis.

Water Transfer Plans

During the presidency of Mohammad Khatami, a native of Iran’s central Yazd province, which borders Isfahan, the plan to transfer water from the Zayandehrud River to Yazd was implemented. In 2000, the Zayandehrud experienced a significant drought for the first time in recorded history. Then the water transfer project expanded to other cities such as Kashan – a project that continues to expand with the digging of new tunnels. But similar projects did not end there; the expansion of unskilled agriculture, encouraged by the government, led to the drilling of numerous wells, each of which has led to water depletion.

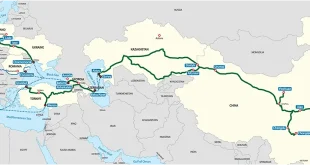

Consisting of four primary lines of water supply and an increasing number of desalination plants, Iran’s water-transfer plan is in process. It is expected to generate approximately 70,000 jobs and be completed by the year 2025, with an estimated cost of $285 billion. Unfortunately, these trends cannot detract from the broader trend that Iran is drying up. Prior to the sanctions placed on Iran in 2000, 1.2 percent of Iran’s annual water supply was consumed in the fields of industry and mining. It was predicted that this percentage would increase to 3 percent by the end of 2021. The rivers in Isfahan, a central province in Iran and which hosts many heavy industries, are on the verge of drying up.

The first pipeline of water from the Persian Gulf to the provinces of Hormozgan, Kerman, and Yazd was fully inaugurated a few months ago. This project has unquestionable benefits to the Iranian economy; the employment potential created during its construction is estimated at 16,000 people. In the second pipeline, there is a plan to transfer water from the Persian Gulf to the provinces of Kerman, South Khorasan, and Khorasan Razavi. With a length of 1,550 km and including 18 water pumping stations, this project will create an additional 30,000 jobs. Similarly, the third pipeline will transfer Persian Gulf water to the provinces of Yazd and Isfahan. This 910 km long project with 10 sections of water pumping stations, has been implemented and will create employment for 14,000 people.

The Political Consequences

Social unrest and instability in the largely-Arab Khuzestan is nothing new to Iran. In 1979, separatist elements in the province rose up against the newly-instated “Islamic Republic.” In 1980, when Saddam Hussein invaded Iran, he started with Khuzestan, hoping in vain that the province’s Arabs would join him; Khuzestan was a major front line in the war for the next three years. More recently, in 2005, Ahvaz, the capital, was bombed by Arab rebels, and in 2011, 15 people died as a result of the government’s interventions to suppress Arab-inspired riots.

Iran’s focus on autarkic self-sufficiency, which has led it to grow food products domestically instead of importing them, is one of the causes of the water crisis in Iran. Meanwhile, most of the country’s important industries are in the central provinces, even though such industries, which are usually water-intensive, would have greater access to water supplies in the country’s coastal provinces. The concentration of industries in the central provinces has been in line with the policy of centralization and with the interests of some political and economic groups, which have created a domestic constituency within Iran. Water transfer projects to the central provinces are also done in the same direction, with special attention to the central provinces. For example, Khuzestan and Ardabil Provinces have, to a large extent, protested against water shortages and complained that their water has been shipped inward; these protests have been faced with violence by the security forces, but have continued. Meanwhile, the water crisis has risen to become the most significant political issue in Iran and has been heavily covered by all media in the country.

Given the protests of the people of Isfahan and the special attention of the Iranian government to the central provinces, it seems likely that the government will implement a water transfer plan to deal with the water crisis. However, the question remains: when Isfahan province is facing a water crisis, why are water-intensive agricultural products, such as rice, continuing to be cultivated in the province? At the same time, while there is a water crisis in most provinces of Iran, it seems that the priority to solve the water crisis is focused on the central provinces.

Additionally, the violent treatment of people protesting the water crisis, especially in Khuzestan and Isfahan, shows that the government does not have a comprehensive plan to solve environmental problems, mainly the country’s water scarcity crisis. In the short term, transferring water to the central provinces may solve part of the water crisis in these areas, but in the medium term, the water crisis will be Iran’s biggest security challenge. The problem is also bound to affect Tehran’s international relations, as it shares water resources with Afghanistan and Iraq and has increasingly butted heads with them in light of shortages. Balanced and sustainable development has not been the focus of the Iranian government, attention to the central provinces has increased the scope of the crisis, and the severity of the border provinces is strongly felt. The government may not be able to solve the water crisis in Iran in general, but to use knowledge and the technology of developed countries in dealing with the water crisis requires interaction with the world, and sanctions, whatever their perverse effects may be, cannot be used by the government as an excuse for inaction on, or poorly implemented solutions to, the water crisis.