Introduction

Despite its abundant oil and gas reserves, over the last four decades Iran has not been able to play a prominent role in the global energy market. According to energy industry statistics, Iran requires at least US$160 billion in investment to continue to export its oil and natural gas. [1] There are many reasons why the Islamic Republic is in such a dire situation. Instead of investing in its energy industry, Tehran prioritized national defense, spending heavily on nuclear missile and drone programs meant to deter its enemies. The crippling sanctions on Iran also caused many foreign energy companies to withdraw from the country, thus creating further obstacles.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has had a severe impact on the energy market. The West’s sanctions on Moscow has resulted in an energy crisis as well as severe inflation in Europe. This could represent an opportunity for Iran to revive its energy industry. Iranian President Ibrahim Raisi’s administration has even suggested that the Islamic Republic could play a role in Europe’s energy security, given its vast oil and gas reserves. [2]

No longer able to sell to the lucrative European market, Russia now finds itself in direct competition with Iran in secondary energy markets such as Asia, Africa, and India. To compete with Russia, Iran might be motivated to finalize a new nuclear agreement and reinstate the conditions of the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear pact. This would remove sanctions on Iran’s oil sales and allow it access to the global market. Russia has already cut into Iran’s share of the energy market in China, where Iran sells most of its oil. [3]

The players: China, Russia and Iran

Russia is the second-largest exporter of crude oil in the world with a revenue stream of US$123 billion annually. In 2021, crude exports accounted for 45% of the nation’s federal budget, and 34% of total European oil imports (4.5 million barrels/day) originated in Russia, according to International Energy Agency data. [4] However, the West limited their purchases of Russian oil in response to Russia’s war in Ukraine, causing a dramatic drop in this volume of oil with major consequences in the European power sector.

Iran has been under various sanctions since the Islamic Revolution in 1979. To maintain its share in the market and continue its foreign exchange income, Iran has used various methods to circumvent sanctions. After former U.S. President Donald Trump levied economic pressure on Tehran in 2018, Iran’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Javad Zarif, said that Iran had “a Ph.D. in sanctions busting.” When asked who else Iran might consider selling oil to, Zarif added: “If I told you, we won’t be able to sell it to them.” [5]

The sanctions against Russia have prompted them to try and sell to markets outside of Europe. This has led to competition with Iran in the lucrative Chinese market. Though Iran has remained stoic — Minister of Oil Javad Owji has stated that Iran will keep selling its oil at a fair price and that the nation has its eye on new markets — some Iranian newspapers reported a decrease in the share of Iranian oil in China’s energy portfolio. [6] According to Sayyed Hamid Hosseini, the President of the Iranian Oil, Gas and Petrochemical Products Exporters Union, Iran would do well to re-establish the JCPOA, which could facilitate the movement of 600,000 b/d of oil to Europe, and be mindful that Iran’s share of the Chinese market may soon shrink. [7]

By 2020, Iran was only able to sell oil to China outside of official channels in the so-called “gray market.” According to OPEC, Iran earned US$12 billion from oil exports that year by selling to organizations or people who were not primarily responsible for oil production, refinement, or distribution. Iran’s crude exports fell to as little as 100,000 b/d at times in 2020 from over 2.5 million b/d in 2018, according to tanker trackers. [8] (NB: As Tehran does not release sensitive data such as oil exports, this data is collected via tanker-tracking companies that use satellite data, port loading data, and human intelligence to make their best estimates).

The British Petroleum’s Statistical Review of World Energy states that despite sanctions in 2021, Iran’s oil production increased by 540,000 b/d (16.1%). [9] The report also states that Iran’s crude production increased from 2.73 million b/d in 2020 to 3.17 million b/d in 2021. This increase came while OPEC members saw a rise of 2.6% in total production in the same year. Iran’s production accounted for 4.1% of global oil output, and the nation saw the second-highest increase in oil production that year. [10] Part of Iran’s oil revenue growth in 2022 was due to rising world oil prices and partly due to the growth of the country’s oil exports. [11]

Exports from Russia to China have been a big challenge for Iran. Most of Iran’s oil continues to go to the Far East, and eventually China, although Iran also helps Venezuela export its oil. [12] The analyst firm Vortexa puts Iran’s exports to China during December 2022 at a record high of 1.2 million b/d, a 130% year-on-year increase. Most of these shipments terminated in Shandong, where for the latter half of 2022 refineries were working with discounted margins amid low domestic demand, prompting a need for discount-grade oil. [13] Senior Kpler analyst Homayoun Falakshahi noted that Iran has seen a large increase in energy exports over the past 12 months, despite continued U.S. sanctions, and that Iran’s average daily exports of gas condensate and crude were up 35% year-on-year to 900,000 b/d last year. [14]

Iran has positioned itself as an alternative gas source for Europe to boost its leverage in nuclear discussions. Foreign Ministry spokesman Nasser Kanaani reminded interested parties in October 2022 that Iran had the world’s second-biggest reserves and therefore the ability to supply Europe. [15] Mohammad Marandi, the advisor to the Iranian negotiating delegation in the nuclear talks, went so far as to warn Europe in May 2022: “Iran will be patient …winter is approaching, and the EU is facing a crippling energy crisis,” a sentiment echoed by Owji in October 2022. [16]

Between August 2022 and January 2023, gas usage across Europe dropped by 19.3% compared to the previous five-year average. The Iranian warnings of a harsh winter did not bear out, and the milder-than-expected temperatures reduced household demands while high prices limited industrial production. Simultaneously, governments launched urgent policies to limit the impact of the energy crisis, sparked by the cessation of deliveries from Russia. [17]

Partnership with Russia

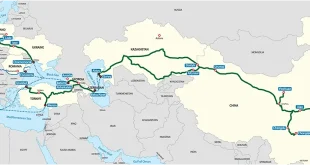

After the onset of the war in Ukraine, Russia was forced to look at alternative markets to sell its energy, with one of the options being to use the capacity of its neighbors, including Iran. Russia said that the European sanctions represented “a key opportunity for the Islamic Republic” to increase the amount of the surplus gas they import through Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. The National Iranian Oil Company has also agreed to partner with Russia’s Gazprom in a deal worth more than US$40 billion in 2022. The agreement with Gazprom allows Iran to increase the amount of gas from Russia it imports from 30 billion cubic meters (bcm) to 55 bcm per year, a significant percentage of Russia’s yearly surplus, estimated to be between 75 bcm and 95 bcm. Russia’s surplus is expected to rise 66% next year and reach 90% in 2027 should EU sanctions continue. [18]

The Iranian Oil Ministry has declared that it will soon import 9 million cubic meters (mcm) of Russian gas per day via Azerbaijan. Additionally, Iran is to receive 6 mcm of gas per day under a swap agreement allowing Iran to export its own gas to other countries from the south. Iran has also announced the signing of gas contracts with Russia worth approximately US$6.5 billion. Owji stated that the country will import Russian gas while simultaneously shipping domestic production to international markets. [19]

Chief Executive Officer Mohsen Khojste Mehr said that in order to increase Iran’s production capacity, the government invested US$15 billion into its South Pars field and US$10 billion into the development of the joint fields of Arash and Farzad. “The development of six oil fields, including Mansouri, Ab Timur, Karanj, Azar and Changuleh, will also be one of the axes of cooperation with Russia,” Mehr said. He added that Iran and Russia will also collaborate on gas and petroleum product swaps, LNG projects, the construction of gas export pipelines and scientific and technological R&D. [20]

Mehdi Safari, Deputy Minister of Economic Diplomacy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, says that about US$6.5 billion of the MoU with Russia’s Gazprom Company have been converted into contracts, and that the rest of the memorandums will be converted into contracts within the coming months. The MoU between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Russian Federation is expected to be signed by September, according to the Iranian Oil Ministry. [21]

As part of the MoU, Russian companies are scheduled to build gas transmission pipelines inside Pakistan, and Iran will assume the role of intermediary for the transfer of Russian gas to Pakistan. [22] In justifying Iran’s cooperation with Gazprom, Safari said: “In addition to economic benefits and reducing the cost of gas transit from the south of Iran to the north to supply fuel to the northern provinces, the Russian gas swap will increase political solidarity between the countries of Iran, Russia and intermediate countries including Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan.” [23]

The state of the JCPOA

Nuclear talks have stalled, and it is unclear if sanctions against Iran will be removed. Should they be lifted, it would still take time for the country’s oil and gas industry to bounce back. While Moscow is not keen to see a reduced share of the global market, it is willing to enter into a temporary agreement with Iran so that both states may work around sanctions imposed on them. For its part, Tehran should not rely on agreements with Russia to bring about the necessary technological support needed for its gas and oil projects, nor should it expect Russia to meet all its gas and oil needs. If sanctions against Iran are removed, Russia will be able to invest in the country’s fields and seek to assert control over the supply routes. [24]

Current discussions and diplomatic efforts center on JCPOA negotiations and the prospective lifting of sanctions, but there are significant roadblocks to an agreement. Divergent priorities, arguments over terms, and the involvement of diverse stakeholders have impacted the pace of discussions. The complicated process involves political agreement, compliance with legal requirements, and consideration of regional and global interests, all of which require due diligence from the parties involved.

Iran needs to focus on creating trust if it wants to allay foreign fears over the easing of sanctions. The Islamic Republic will need to give explicit and verifiable assurances regarding their nuclear program, allow foreign bodies to conduct inspections, and stick to severe restrictions on uranium enrichment if they want sanctions lifted. Additionally, Iran will face restrictions on their missile development, testing, and proliferation, including caps on the payload and range of missiles, as well as the development, export, and use of drones. To foster confidence, Iran could also promise to abstain from aiding proxy forces or non-state actors and contribute to regional security and non-proliferation.

Even if the JCPOA is restored and sanctions are lifted, it will not be easy for Iran to return to the marketplace. India, for example, currently has an embargo on Iranian oil, so Moscow would need to negotiate with New Delhi to allow Iranian oil exports to resume. The terms of any oil exchange deals between Iran, Russia, and India would be complicated. Stakeholders would include governments, oil firms, and international organizations, and an agreement would require the input of experts in energy markets, geopolitical analysis, and global commerce. Further complicating such a deal is the fallout from the current war in Ukraine. Not only will the parties face political pressure from the West, but the economics have been altered with Russia’s target market switching from the West to the East. Western sanctions have forced Russia to sell oil at a lower price to India and Turkey, and this will make it more difficult for Iran to compete. [25]

Energy markets in the aftermath of the war in Ukraine

Russia’s war in Ukraine has set off a chain reaction of events — sanctions against Russia by the EU, the reduction of Russian gas exports to Germany, and the suspension of the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline — that has caused turbulence in the global energy market. Iran miscalculated how these events would play out, and Mohammad Ghasemi, the head of the Research Center of the Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture of Iran, considers them to be the big loser of the war in terms of energy. [26]

Ebrahim Raisi’s administration believed Europe would face a harsh winter and cause a spike in demand for oil, which would allow Iran to use its energy reserves as a trump card to force Europe to more flexible in JCPOA negotiations. The winter, however, turned out to be mild and Europe and its partners chose not to revive the JCPOA. Tehran also failed to predict how the EU’s sanctions would drive Russia to new markets, and that Moscow would be able to offer gas to countries such as China, India, and Turkey at cheaper prices than Iran. As a result, Iran has suffered losses in the energy market in the past year. [27] Because Iran and Russia are now competitors in the energy market, Russia will only invest in projects that it is sure will not cause a reduction in their share of the energy market.

Further barriers to resurrecting the nuclear deal have been disagreements over topics such as the extent of Iran’s nuclear program, the degree of sanctions relief, and the method for ensuring Iran’s compliance. Negotiations have been complicated and involve many issues not made public. These could include shifting global dynamics, stakeholder influence, worries about local security, and priorities between the participants to the negotiations, but it is difficult to find trustworthy sources who will give an accurate and complete picture of JCPOA negotiations. [28]

Conclusion

Iran’s energy sector has been significantly impacted by Russia’s war in Ukraine. The conflict has had a number of direct and indirect effects that have altered Iran’s energy environment. The war has disturbed international energy markets and created oil price volatility. Given that Ukraine is a key transit country for Russian gas supplies to Europe and that Russia is a significant energy actor, the conflict has raised questions and worries about the reliability of energy supplies. Iran, whose primary source of income is oil exports, has been impacted by these price changes. The war has also raised geopolitical dangers in the area, which has an impact on Iran’s energy security. Concerns about the security and stability of energy supply lines and infrastructure have grown as tensions have increased.

Additionally, the dynamics of global partnerships and alliances have changed as a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Alternative energy supply channels and collaborations are being investigated as nations look to diversify their energy supplies and lessen their reliance on Russia. For Iran’s energy sector, this change offers difficulties and opportunities. Iran may be in a position to expand its energy partnerships with other nations and draw in capital, but it may also experience more competition on the international energy scene.

Finally, the energy sector in Iran has been significantly impacted by the Russia-Ukraine war. The upheavals in the world energy markets, the implementation of sanctions, increased geopolitical risk, and shifting alliances have all made the environment for Iran’s energy industry unclear and difficult. To overcome these obstacles and secure the long-term stability and expansion of Iran’s energy sector, strategic planning, flexibility, and the exploration of alternative alliances are all required.

References

[1] Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture, “Iran Oil, Gas Industry Needs $160 Billion of New Investment: Minister,” November 2, 2021, http://bitly.ws/BXeu. [2] Andrew Parasiliti and Elizabeth Hagedorn, “The Takeaway: Iran Deal May Come Too Late to Stave Off Energy Crisis in Europe,” Al-Monitor, August 17, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXeH. [3] Nadeen Ebrahim, “Ukraine War Threatens Iran’s Last Economic Lifeline,” CNN, May 27, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXeS. [4] Smruthi Nadig, “One Year On: How the Russian War Has Affected Its Exports,” Offshore Technology, February 24, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXf2. [5] Michelle Nichols, Lesley Wroughton, and Phil Stewart, “Exclusive: Iran’s Zarif Believes Trump Does Not Want War, but Could Be Lured into Conflict,” Reuters, April 25, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXfq. [6] “Iran Selling Crude Oil at ‘Good Price:’ Min.,” Shana Petro Energy Information Network, May 18, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXfK. [7] “Iran May Lose Its Share in China Oil Market: Official,” Iranian Labour News Agency, July 24, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXfW. [8] Alex Lawler, Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, and Chen Aizhu, “Iranian Oil Exports End 2022 at a High, Despite No Nuclear Deal,” Reuters, January 15, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXh9. [9] British Petroleum, Statistical Review of World Energy 2021, June 5, 2023, http://bitly.ws/IZyx. [10] “Iranian Oil Output Surges 16% in 2021: BP,” Tehran Times, July 2, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXgE. [11] Dalga Khatinoglu, “OPEC Announces Tripling of Iran’s Oil Revenues in 2021,” Radio Farda, June 28, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXgf. [12] Alex Lawler, Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, and Chen Aizhu, “Iranian Oil Exports End 2022 at a High, Despite No Nuclear Deal,” Reuters, January 15, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXh9. [13] Ibid. [14] Michael Lipin, “Q&A: Iran Likely Grew Oil Exports by 35% in 2022, Data Company Says,” Voice of America, January 18, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXhA. [15] Shabnam von Hein, “Iran Faces Gas Shortage Despite Vast Reserves,” Deutsche Welle, January 14, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXhL. [16] Kate Abnett, “Europe Slashed Winter Gas Use amid Energy Crisis,” Reuters, February 21, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXhT. [17] “Iran Nuclear Deal ‘Imminent’ with Crippling Sanctions Removed,” Al Jazeera, August 19, 2022, http://bitly.ws/IZCp. [18] Dalgha Khatinoglu, “Iran Wants to Import 55 Million Cubic Meters of Russian Gas Per Day,” Deutsche Welle, May 10, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXiq. [19] “Iran Signs $6.5 Billion Gas Contract with Russia, Gas Swap Deal Reportedly Being Finalized,” Business Insider, November 1, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXiB.[20] “$40 Bln Investment Deal Signed between Iran’s NIOC, Russia’s Gazprom,” Tasnim News Agency, July 19, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXi6.

[21] “Iran, Russia to Ink MoU Worth $40 Billion in Coming Months: Oil Minister,” Tasnim News Agency, May 19, 2023, http://bitly.ws/IZD7. [22] “Iran Wants to Work with Russia’s Gazprom to Build Gas Pipelines to Pakistan & Oman,” Silkroad Briefing, July 28, 2022, http://bitly.ws/IZDw.

[23] Morteza Ahmadi Al Hashem, “Iran-Russia to Ink Contract Worth $40bn Next Week: Safari,” Mehr News Agency, November 2, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXic. [24] Umud Shokri, “The Future of Iran-Russia Energy Relations Post-Ukraine Crisis and Iranian Nuclear Talks,” Mena Affairs, September 15, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXiK. [25] “Zero to 100 Swap and Transit of Russian Oil from Iran/Opportunity for Cooperation of Sanctioned Parties in the Energy Market,” Fars News, October 2, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BXjr. [26] “Is Iran a Big Loser in the Russia-Ukraine war?” Farday Eghtesa, February 21, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXjL. [27] “Incorrect Foresight in the Government’s Analysis Has Reached the Gas Sector too. Why Was ‘Hard Winter’ Imposed on Iran instead of Europe? A Leader Amid Uninformed Advisors?” Khabar Online, January 25, 2022, http://bitly.ws/IZFo. [28] “Is Restoring the Iran Nuclear Deal Still Possible?” International Crisis Group, September 12, 2022, http://bitly.ws/IZF9.