After the withdrawal of the United States from the 2015 “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action,” or JCPOA, nuclear deal with Iran, Tehran initially indicated that it would continue to follow its obligations in cooperation with the remaining members of the “P5+1” group that had negotiated the deal. Despite this early indication, Iran gradually reduced some of its commitments and, contrary to the nuclear deal, increased both the level of uranium enrichment and the number of centrifuges in its nuclear facilities. In January 2021, Iran wrote a letter to the International Atomic Energy Agency announcing its plan to “enrich uranium to 20 percent purity.”

Tensions have risen recently between Iran and the Middle East countries, which are suspicious of its nuclear activities. The Israeli government has earmarked $1.5 billion for the military’s readiness to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities. In November, Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council Ali Shamkhani shared on his Twitter account, “The unauthorized US President (Joe Biden) is not ready to give guarantees. If the current situation does not change, the outcome of the negotiations is clear.” The parties to the nuclear agreement started negotiations in Vienna, the capital of Austria, on April 6, and the talks were suspended at the end of June after the election of the new hardliner President Ebrahim Raisi. Meanwhile, in Iran, unlike the previous government, the conservative administration of Raisi so far seems distant from the West and argues that the nuclear agreement did not benefit the country.

President Joe Biden had promised during the U.S. presidential election that he would return to the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran if he won the election. However, this promise was contingent on Iran agreeing to return to the deal as well. Iran’s actions prevented Biden from easily doing so. During the final months of Hassan Rouhani’s presidency, two rounds of nuclear negotiations took place between Iran and the P5+1, but both failed, and by the summer, Tehran indicated that the deal should instead be made with his successor in office, arch-conservative cleric Ebrahim Raisi. Negotiations under Raisi have gone little better, due in part to Iran’s insistence that the United States lift all post-2017 sanctions against the country as a precursor to negotiations – a demand that U.S. and other European countries have rejected. During the Trump era, and under his “maximum pressure” policy, many sanctions were imposed against Iranian financial institutions, oil exports and members of its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). These sanctions were instituted both in response to its nuclear program and its regional foreign policy; Biden’s officials insist that the two are separate issues, while Raisi refuses to recognize a distinction.

Slow, Uncertain Progress

All nations involved in the negotiations, including both Iran and the P5+1, could be impacted by the disputes over the nuclear program. If nations lose hope that the nuclear deal can be revived, then Iran will likely persist in restricting the scope of any potential agreement. At the same time, Tehran will bring into effect advanced centrifuges and test various techniques to convert the uranium it will accumulate to more highly enriched uranium that could be utilized in producing a bomb.

Sanctions have gravely impacted Iran’s economy – not only by the dramatic increase of inflation and prices, but also by additional waves of the Covid-19 pandemic, which sanctions have restricted Iran’s ability to fight. Although the new government has expressed its intention to curb inflation and provide citizens with employment and accommodation, these goals do not seem to be reachable without an easing of sanctions. In spite of this, Iran’s leaders seem insistent on pursuing their current combative diplomatic approach. Ebrahim Raisi has expressed his advocacy of an autarkic “resistance economy,” a concept supported by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

Former Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister and current chief negotiator for Iran’s nuclear program, Abbas Araghchi, announced in early April that 60 percent enrichment had begun in Iran. Two days after the news, the Natanz enrichment facility was heavily damaged in a sabotage attack, widely thought to have been the work of Israeli agents – a conclusion that Araghchi himself espoused in a letter to the Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency. The U.S. Special Representative for Iran on the future of Iran’s nuclear program had said that if Iran did not return to the IAEA at the end of the nuclear talks and came “very close” to building a nuclear bomb, the United States would pursue alternative options to constrain its program, not ruling a “Plan B” as a possible step. The urgency of such action has been amplified by Iran’s progress with respect to enrichment, enabling Tehran to produce weapons-grade uranium.

On the eve of the seventh round of nuclear talks and following the publication of a recent report by Rafael Grossi, Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency, on Iran’s refusal to re-install surveillance cameras at the Karaj centrifuge assembly facility, Kazem Gharibabadi, Iran’s Ambassador Permanent Representative to the UN in Vienna, tweeted, “It is deeply unfortunate that after three terrorist sabotage operations at Iran’s nuclear facilities over the past year, the IAEA is still carrying out these heinous acts, contrary to numerous resolutions of the IAEA General Assembly and the UN General Assembly, and even because of equipment and property.” On Wednesday, December 15, Grossi confirmed reaching an agreement with the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran regarding the installation of new surveillance cameras.

The View Around the World

Mikhail Ulyanov, Russia’s permanent representative to the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), who took part in the UN Security Council talks, wrote in a Twitter message: “Let alone complicate the situation with Iran’s nuclear program, as well as the lifting of sanctions.” In an interview with Russian TASS news agency on Monday, December 12, Ulyanov said that progress was being made in the Iran nuclear talks, but it had been slow and cumbersome, raising frustrations in Washington, Tehran, and Moscow. “What can we do with these centrifuges?” he asked. One option, he noted, was to move them out of Iran. Another option was to destroy them; yet another was to store and seal them under the auspices of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman said in a press conference, “the US should lift all illegal unilateral sanctions against Iran, China and other third parties, and Iran should resume fulfilling its nuclear commitments on this basis.” According to Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian, although there was no opening in the talks, all parties were serious and agreed to return to the UN Security Council in good faith. According to a document reached in the previous six rounds of talks, the two sides had comprehensive and in-depth talks on lifting sanctions and nuclear issues, and Iran submitted amendments in both areas to the original text.

As hopes for a resumption of the JCPOA in Vienna waned, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said the country was preparing “alternative ways” to deal with the Iranian threat if the Vienna talks fail. During a visit to Indonesia on November 14, he said that Washington would continue the diplomatic process with Iran and considered it the best option for progress but was also “actively looking at other ways with our partners and allies.” In this regard, the head of U.S. Central Command, General Kenneth McKenzie, stressed that Washington had a variety of strong military options on the table to “stop Iran.” “If rapid progress is not made, the UN Security Council will reach an agreement,” he said.

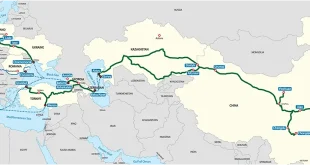

According to the Iranian delegation in Vienna and the statements of Iranian officials, it seems that Iran is in no hurry to reach an agreement. Last week, Ebrahim Reisi sent his administration’s first general budget to the Iranian parliament for approval. The important point of next year’s Iranian budget was the expected returns from oil exports. For the next year (starting in March 2022), the government has set a daily sales target of 1.2 million barrels of oil, the assumed price of which is set at $60 per barrel. Some experts have contended that Iran wants to put more pressure on the West by scaling up uranium enrichment and increasing the number of centrifuges, then promising to lower them once more in exchange for a lifting of sanctions. From Tehran’s security point of view, deterrence, would prevent the West from hindering Iran’s progress and development in all dimensions. At the same time, Iran has pursued more conventional diplomacy in other directions in case current Vienna talks failed to revive a nuclear deal. The Raisi administration is finalizing a 20-year comprehensive cooperation agreement with Russia, similar to its earlier agreement with China – although Moscow and Beijing each oppose Iran’s nuclear program, albeit to a lesser degree than Washington. In conclusion, current negotiations in Vienna are another proof of what Iran has shown over the past four decades; that development has come second to deterrence in the government’s strategic calculations. https://gulfif.org/