A new agreement to import Russian gas through Azerbaijan – signed by Iran’s president in Moscow — may reflect difficulties in constructing a pipeline under the Caspian Sea.

Among the many challenges it faces as its regional alliances buckle, Iran is also experiencing a severe energy crisis despite possessing the world’s second-largest gas reserves.

This crisis has led to widespread disruptions across households, manufacturing and power plants. Last fall, there was a daily gas shortfall of 90 million cubic meters (mcm). The gap between production and consumption is projected to rise to 300 mcm this winter.

Growth in gas production has slowed to about two percent annually over the past three years compared to five percent annually in the previous decade. At the same time, consumption has surged. Shortages are exacerbated by aging infrastructure, particularly at the South Pars gas field, which accounts for 75 percent of Iran’s gas production, coupled with sanctions that limit access to advanced technology and expertise. Experts estimate that reviving Iran’s oil and gas sector will require at least a $250 billion investment.

Among the consequences of the crisis are frequent power outages, petrochemical refineries running at only 70 percent capacity, and a 45 percent decline in steel production. There are also major negative impacts on Iranians’ health, with Iran’s growing reliance on cheap dirty fuel oil called mazut leading to severe air pollution.

In part in response to these shortages, the National Iranian Oil Company and Gazprom, a Russian-controlled energy company, inked a $40 billion memorandum of agreement in July 2022 with the goal of facilitating the development of oil and gas fields offshore.

A new agreement to import Russian gas through Azerbaijan was signed by Russia and Iran during the recent visit of Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian to Moscow.

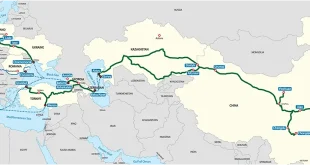

Construction of a gas pipeline from Russia to Iran is under way, Russian President Vladimir Putin said at a press conference after talks with Pezeshkian. “The North-South corridor and the gas pipeline to Iran are two ongoing projects that are both highly significant and fascinating,” Putin said. “Regarding the potential delivery levels, we think that we should begin with modest amounts, up to 2 billion cubic meters, and eventually increase the amount of gas delivered to Iran to 55 billion cubic meters annually,” he stated.

Following a decrease in gas imports from the European Union as a result of the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, Russia is attempting to diversify its energy markets. Gas deliveries to Iran could augment a bilateral relationship with a large and growing arms and security dimension. But there are many hurdles to overcome.

Iran’s natural gas production has experienced fluctuating trends in recent years. Production rose from 262.3 billion cubic meters in December 2022 to 275 billion cubic meters in December 2023. However, the nation saw a slight decline in output over the previous five years, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of -0.03 percent. The outlook for the future is more optimistic, with projections indicating a 3 percent CAGR from 2024 to 2028. This disparity between historical performance and future expectations underscores the challenges facing Iran’s natural gas sector, including inadequate investment, technological constraints, and the impact of international sanctions. Nonetheless, the anticipated growth signals the potential for improvement if Iran addresses these hurdles and leverages its vast reserves alongside planned investments in exploration and production activities.

To deal with current shortages, government officials have proposed rerouting gas exports to domestic power plants and encouraging the modernization of vehicles and public transportation. Iran’s then oil minister Javad Owji announced in July, 2024, that Iran would import 300 mcm of Russian gas per day through a projected Caspian Sea pipeline. Iranian officials hope to establish Iran as a regional gas hub by re-exporting the Russian gas to Pakistan, Turkey, and Iraq.

The memorandum of understanding between Iran and Russia reflects their growing geopolitical alignment. They want to subvert Western hegemony in energy markets by working together in platforms such as BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to create alternative energy corridors. The global energy trade structure may be further upended by initiatives to use local currencies, which would lessen dependency on the U.S. dollar.

By establishing new routes and fortifying connections between countries with abundant energy resources, the gas agreement between Russia and Iran has the potential to change the dynamics of energy commerce. However, Iran’s ambitions to become a regional gas hub are called into question by its reliance on imported gas to meet local demands. Uncertainty is further increased by growing geopolitical tensions, infrastructure weaknesses, and possible additional sanctions that are likely if the new Trump administration imposes “maximum pressure” 2.0 on Iran.

There are other serious concerns about the deal’s economic viability. Given its decreased hard currency receipts because of sanctions, Iran’s capacity to pay for significant gas imports is in question. There are practical and geopolitical challenges to reselling excess gas to nearby nations like Iraq, Turkey, and Pakistan. Complex regional dynamics and the creation of new infrastructure to support these secondary exports are essential to the strategy’s success. Furthermore, the magnitude of Iran’s domestic energy problems is underscored by the anticipated volume of Russian gas imports, which would account for nearly one-third of Iran’s daily production.

In addition, the legal and regulatory framework for such a large gas trading deal is still unclear. A key part of the July agreement was to build a new pipeline beneath the Caspian Sea, which Russia is supposed to pay for. However, there are technical as well as political constraints to laying pipelines beneath the Caspian, an area with complex geological and ecological aspects.

Russia and Iran have now decided to build a gas pipeline through Azerbaijan, perhaps as a substitute for a subsea pipeline across Turkmenistan or the Caspian Sea. The land route seems more practical because it would be less expensive to build and maintain and not require approval from all Caspian nations. Azerbaijan could become a hub for gas exchange, increasing its strategic significance in the North-South corridor.

Another crucial issue is the cost of gas supplies to Iran. There are questions about the cost-effectiveness of shipping gas from Russia’s Siberian reserves to Iran.

It is also unclear if Russian supplies can solve Iran’s long-standing energy problems. Underinvestment in infrastructure, systemic mismanagement, and foreign sanctions will be hard to overcome and could impede the project’s success.