There is a concern in Iran that Azerbaijan intends for the project to block Iran’s border with Armenia as the proposed route of the Zanzegur Corridor project runs along the full length of the border.

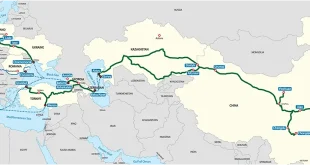

The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, fought from September to November 2020, ended with a significant victory for Azerbaijan over neighboring Armenia and its recapture of much of the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region. The two countries signed a tripartite ceasefire agreement, shepherded by Russia, which provided for the opening of transport routes. In particular, Azerbaijan has pushed to establish the Zanzegur Corridor project, a proposed transport corridor that would link it to the Nakhchivan Autonomous Region, a western exclave of Azerbaijan separated from the rest of the country by Armenian territory. Azerbaijan strongly argues that Article 9 of the ceasefire allows for the corridor’s opening, and Baku has previously voiced its plans to rebuild the region’s Soviet-era railways and highways to better connect Azerbaijan to Nakhchivan. The proposed Zanzegur corridor is also part of a larger transportation project connecting Baku to Istanbul in European Turkey. In a more general sense, this corridor is a geopolitical project intended to connect Europe to Central Asia and China through Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Azerbaijan Claims Economic Benefits for All Sides

When completed, the Zangezur corridor will be a significant transit route linking Baku and Kars, a provincial capital in eastern Turkey, via Armenian land. Because it must traverse Armenian territory but without Armenian checkpoints or border controls, it will first be necessary to reach prior full agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Azerbaijan argues that both countries will benefit from the project’s completion, as it will develop links between Europe and Asia and join Turkey, Russia, Iran, Armenia, and Azerbaijan in one economic corridor, facilitating trade for all. Although Russia and Turkey, a NATO member, have opposed one another over the conflict in Ukraine, it seems that they can agree on the positive impact opening the Zangezur corridor will bring. Moreover, while sentiment against the corridor has increased in Iran, some of its politicians are in favor of its construction and believe that Tehran could benefit from the increased trade and political integration it would bring.

Of all the countries, Azerbaijan—which would link its two parts with the corridor’s construction—stands to benefit the most. If the corridor opens, Azerbaijanis would no longer need to pass through Iran in order to travel to Nakhchivan, lessening Tehran’s influence (and leading some Iranian officials to oppose the project). The corridor will also directly link mainland Azerbaijan to Turkey. Tehran believes that Baku views this project would bring Turkish, even Israeli, guarantees should Azerbaijan enact anti-Iranian policies. There is concern in Iran that Azerbaijan intends for the project to block Iran’s border with Armenia as the proposed route of the Zanzegur Corridor project runs along the full length of the border.

On the other hand, because tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan have negative consequences for Tehran, the corridor’s completion, and accompanying political stability and economic development in the Caucasus, should have significant economic benefits for Iran. Moreover, the security of the transit route will be in the interest of Iran and should be welcomed. Iran would also gain a security advantage; if Azerbaijan and Armenia are at peace, Iran would reap the benefits of a peaceful Caucasus region. Moreover, even if Baku is connected to Nakhchivan via the Zangezur route, which is currently still a railway, the Republic of Azerbaijan will probably not abandon the Iran route altogether, because a multiplicity of transit routes. A senior Iranian diplomat who had served as Ambassador to Baku argued that the Zangezur corridor forms part of the East-West transport corridor, and that opening it will not have any impact on the Iranian-Armenian border. Tehran has also displayed some optimism over the redevelopment of Soviet-era roads that have fallen into disrepair. During the sixth annual summit of the Caspian littoral states, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev stated that Azerbaijan had begun to restore East Zangezur and Karabakh after its victory in the war, suggesting the imminent opening of the Zangezur corridor. Under the ceasefire agreement, Armenia is obligated to ensure transport links between the western regions of Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan and ensure that citizens and goods can move freely in both directions. Azerbaijan holds a special position as a dividing point on the South Caucasus middle corridor and will benefit from an enhanced role as the main conduit for East-West and North-South movement in Eurasia.

The Iranian Reaction

There is a different point of view in Iran regarding the Zangezur Corridor. The First Nagorno-Karabakh War, which began in 1990 prior to the Soviet Union’s dissolution, cut off Iran’s railway access to the former Soviet railway network and caused significant damage to Iran’s economy. Tehran could benefit from removing these obstacles as soon as possible; a functioning Caucasian road and rail network would guarantee Tehran access to the entire Caucasus and beyond, particularly through the Jolfa Iron Bridge and the Nakhchivan Railway. If Baku wants unhindered transportation access between its mainland and Nakhchivan, Iran will support it. Moreover, during the last three decades, Iran has not allowed Nakhchivan’s connection with the mainland to be cut off, permitting the citizens of Azerbaijan to travel through Iran. But if there is a specific definition of “Zangezur Corridor,” and according to the interpretation that some in Iran are writing today, a portion of Armenia’s southern Syunik Province would be separated from the control of Armenia in the form of a special legal regime—a situation that many Iranians would oppose.

The Strategic Council of Foreign Relations in Tehran, whose director is Iran’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs Kamal Kharazi, warned against the construction of the Zangezur Corridor in an article titled “Conspiracy to Create NATO’s Turan Corridor.” In that article, the council indicated that the corridor’s completion would have significant geopolitical consequences for Iran, Russia, and China. This corridor has been introduced to NATO’s “Turan Corridor,” a project ostensibly supported by Israel and NATO, and Turkey and Azerbaijan are alleged to want to foment ethnic unrest in the areas of Iran where Turks live by building this corridor. The author of the article believes that NATO’s Turan Corridor is supposed to directly bring NATO onto the northern border of Iran, the southern border of Russia, and western China in Xinjiang and complete the plan to encircle these countries and lay the groundwork for their disintegration. NATO’s presence in the Caucasus and Central Asia complements Russia’s blockade plan from the Black Sea, China’s blockade from the South China Sea, and Iran’s blockade from the Persian Gulf.

Iran’s Path Forward

In the current situation, the best strategy for Iran in the Caucasus region, especially its geopolitical issues, is to establish immediate face-to-face communication with Russia and Armenia and raise specific questions related to the Zangezur Corridor and listen to whether they agree with the implementation of the project or not. Armenia is likely to be concerned about the prospective loss of its border with Iran and react accordingly against the project if that border’s future is placed into question. These issues are also highly important from the perspective of Russia’s military presence in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh and the Armenian government, which is first and foremost concerned with protecting its national sovereignty.

On the other hand, concerns about Turkey’s connection to Central Asia and the strengthening of NATO are not very common among the region’s Arab states. Moreover, during the 70 years that have passed since Turkey joined NATO, Iran has bordered the U.S.-led military alliance, but due to the friendly relations between Ankara and Tehran, it has never suffered any special damage from its proximity. Azerbaijan has not yet made any request to join NATO and doing so would provoke a major perhaps violent Russian reaction. It would also not benefit Azerbaijan in the short run as it would require significant alterations to its military that would take years to complete. Considering the role of nationalism and the influence of nationalists in Iran’s foreign policy, it seems that Tehran’s opposition to the Zangezur Corridor will continue. Yet, it will almost certainly persist with its current foreign policy, which entails disagreement with Azerbaijan and a continuation of recurring tensions.