Importers Benefit, but Transparency Suffers, and Price Gaps Widen with the Spread of Cheap Sanctioned Oil

China’s independent refiners, known as “teapots,” increasingly are replacing Venezuelan crude with Iranian oil. This shift shows how sanctions pressure, commercial reality, and geopolitics now shape global oil flows more than formal rules. As U.S. enforcement has disrupted Venezuelan exports, Iranian crude has emerged as the most practical and profitable alternative for China’s small refiners.

Teapots operate mainly in Shandong province and process a large share of China’s imported crude. Unlike state-owned giants, they depend on cheap feedstock to survive. For years, sanctioned oil from Venezuela, Iran, and later Russia allowed them to stay competitive. When access to one source narrows, they move quickly to another.

Teapots operate mainly in Shandong province and process a large share of China’s imported crude.

That is exactly what happened with Venezuela. In 2025, China imported about 389,000 barrels per day of Venezuelan crude. U.S. pressure then intensified. Washington tightened controls on shipping, targeted shadow fleets, and redirected Venezuelan exports through approved trading firms. These steps sharply reduced the volume of Venezuelan oil reaching Asia. By early 2026, shipments to China were projected to fall by as much as 74 percent, leaving a major supply gap for teapots.

This loss mattered because Venezuelan crude fits teapots’ needs. It is heavy, high in sulfur, and cheap. Replacing it with non-sanctioned oil from Canada, Iraq, or the Middle East would raise costs and squeeze margins. Teapots, therefore, needed another discounted heavy crude that could slot easily into their refineries. Iranian oil fit that requirement better than any alternative.

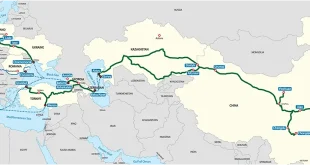

Iranian crude offers clear logistical advantages. Large volumes already sit in bonded storage tanks and on offshore vessels near China. Refiners can access these barrels quickly, with shorter shipping routes and lower exposure to seizures. Venezuelan cargoes, by contrast, face long voyages, frequent rerouting, and growing risks from U.S. interdiction, all of which raise freight and insurance costs.

Quality also plays a role. Iranian heavy and Pars blends closely resemble Venezuela’s Merey crude. They produce similar yields, especially for asphalt and fuel oil, on which teapots rely for profitability. Iranian extra heavy crude delivers comparable results without requiring refinery changes, allowing refiners to switch supply with minimal disruption.

Iranian extra heavy crude delivers comparable results without requiring refinery changes.

Payment terms further tilt the balance toward Iran. Venezuelan oil sales often link to debt repayment arrangements, with billions of dollars still outstanding. These deals draw scrutiny and complicate transactions under U.S. oversight. Iranian sales increasingly use renminbi and pass through Chinese financial channels insulated from the dollar system. This reduces legal and financial risk for buyers. Combined with discounts often exceeding $10 per barrel below Brent, Iranian crude has become the cheapest reliable option available.

China’s government has tolerated and enabled this shift. Beijing rejects unilateral U.S. sanctions and treats energy trade with Iran as a commercial matter. In practice, it allows teapots to import sanctioned oil through shadow shipping, crude relabeling, and flexible quota allocations. This approach gives China access to cheap energy while preserving deniability at the state level.

By 2025, sanctioned crude from Iran, Russia, and Venezuela made up as much as 40 percent of China’s oil imports. These barrels saved China billions of dollars and strengthened ties with governments outside the U.S.-led system. Teapots, while nominally private, operate within a framework shaped by state policy, port access, and financing rules.

For Iran, this demand has softened the impact of sanctions. Despite enforcement efforts and periodic crackdowns, Iran has kept exports around 1.5 million to 1.8 million barrels per day, with China buying the vast majority. Improved ship-to-ship transfers and logistics have reduced delays and helped maintain steady flows, even if at deep discounts.

China’s growing role as the main buyer for sanctioned oil has wider consequences.

At the same time, the shift exposes the limits of U.S. enforcement. Sanctioning vessels and intermediaries raises costs but does not stop trade. Shadow fleets adapt, cargoes get relabeled, and buyers remain shielded from dollar exposure. Research shows that large volumes of sanctioned oil continue to move through these channels despite years of pressure. U.S. actions slow the trade, but they rarely shut it down.

China’s growing role as the main buyer for sanctioned oil has wider consequences. By absorbing Iranian exports, Beijing provides Tehran with revenue that supports its budget and regional activities. China presents itself as a stabilizing power, even mediating between rivals like Iran and Saudi Arabia, while quietly benefiting from discounted energy supplies.

Globally, the spread of cheap sanctioned oil puts downward pressure on prices and fragments markets. Importers benefit, but transparency suffers, and price gaps widen. For sanctions designers, the lesson is clear: targeting producers alone is not enough. As long as large buyers and financial systems remain available, oil will find a way to move.

The teapots’ pivot to Iranian crude is not a temporary workaround. It reflects a durable system in which commercial need, geopolitical alignment, and enforcement gaps reshape the oil market. In that system, sanctions still matter, but they no longer decide outcomes on their own.